The First Nations Land Management Act: A New Approach

January 15, 2018 - Consider a community where you can own a home, but not the land upon which it is built. You can own the structure but there is no guarantee to the land because it is technically owned by the federal government. At any point the government can make decisions about the future use of the land your home occupies. If you would like to access capital or start a business, your home cannot be used as collateral because there is no security in a free-hold structure on land you do not own. Also, the government makes final decisions on your behalf.

This is the case for most Anishinaabe individuals living in First Nations reserves in Canada. In fact, whole communities are restricted in this way. Social and economic development on First Nations reserves is often stagnated by the current property rights processes. Since there is no fee-simple ownership of land, First Nations must deal with the federal government in order to issue certificates of possession, leases and customary lease holdings (INAC , 2016). As a result, First Nations are hampered by weak security tenure and high transaction costs. Costs related to development on-reserve are four to six times higher than they are for comparable municipalities (Greg Richard, 2007).

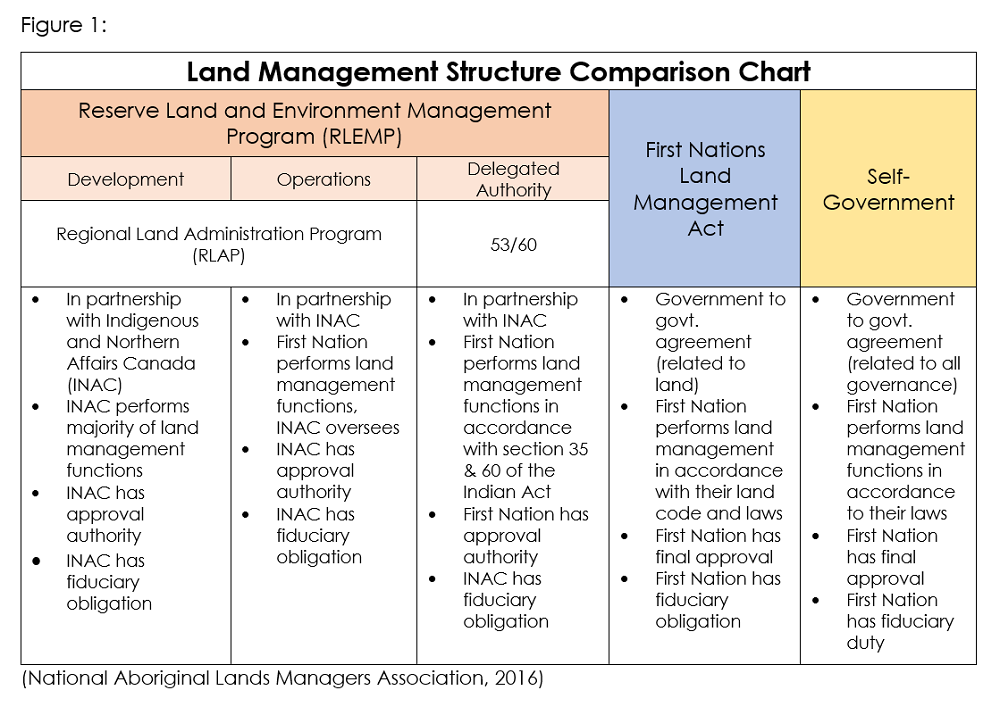

The Indian Act is a federal statute overseeing the status, government, finances, and reserve land of First Nations people and communities. In terms of land management, it establishes that legal title to reserve land is held by the Crown. Under this statute, “No Indian is lawfully in possession of land in a reserve unless, with the approval of the Minister, possession of the land has been allotted to him by the council of the band” (Canada Federal Government, 1985). First Nations govern reserve lands according to the Indian Act, which gives INAC the responsibility of carrying out land management functions, and subjects First Nations to administrative hurdles and inhibits economic development opportunities. There are a number of land management structures in Canada, administered and surveilled by INAC. The structures are listed below in figure 1.

There is, however, one exception to this rule. Cue the First Nations Land Management Act, an agreement made between the Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs and thirteen First Nations on February 12, 1996. The agreement offers a new approach to land management, while not interfering with treaty or constitutional rights of Anishinaabe people. Signing First Nations are empowered to manage their lands outside of the Indian Act, once a land code is ratified[i]. First Nations exercise powers and rights associated to the ownership of land, including granting rights or licenses to land, managing natural resources, and conducting independent transactions. The land code, once in effect, acquires legal standing and becomes enforceable in the Canadian court system (FAFNLM, 1996).

There are First Nations who have opted not to sign FNLMA, under the purview that First Nations have responsibilities to land within the original nationhood agreements. Batchewana First Nation has made this declaration, and in a sit-down interview with Chief Dean Sayers it was shared, “There are nationhood agreements [treaty] in Robinson-Huron, in which we retain underlying title and if those agreements fail they revert back to us.” He continues, “In the assertion the crown makes over lands, which are stolen lands, we find real problems with the First Nations Land Management Act based on that foundation. That premise.” Instead of answering to oppressive policy, First Nations like Batchewana have taken a proactive approach to recognize their responsibilities to traditional territories and he adds, “It’s from that perspective that Batchewana has taken action instead of wading through the quagmire of legal systems in Canada that are set up by the doctrine of discovery, which in its foundation is illegal”. There are benefits to maintaining rights like increased ownership and control, but holding true to responsibilities rooted in the original agreements in the form of treaty is an important declaration to recognize, and we would be amiss not to include.

Bingwi Neyaashi Anishinaabek (BNA) is a First Nation community in the Lake Nipigon area, who signed FNLMA and used the increased control to their advantage. Over 250 band members were displaced from their territory in the 1950s when the First Nations License of Occupation was cancelled by the federal government. Land was returned to BNA in April 2010, and they were tasked with the feat of building a community from the ground up. Beginning from a point of increased control, with the FNLMA and ratification of a land code, has made development much easier for the community. Jeremy Bonhomme, the Land Management and Community Development Officer, says that, “Since the successful ratification of the BNA Land Code, the Community has been able to speed up the development of the Community.” He adds, “This spring, we completed surveying work on two new phases of housing, totaling 42 new housing lots. Through the same project, we were able to survey four additional roads within the community which we will begin construction on next month.”

Large scale time series statistical data is not available on the effects of increased ownership and control, but there are cases of First Nations bands in Northern Ontario who have begun to see the positive effects of the FNLMA, like Bingwi Neyaashi Anishinaabek. Preliminary findings show that participation in the First Nations Land Management Act and ratification of a Land Code reduces drag for on-reserve development. At minimum, it reduces transaction timelines and costs by eliminating the involvement of the federal government.

Additional longitudinal research will continue to highlight the long-term of effects of the implementation of FNLMA, land codes and similar routes to increased ownership and control of land. More regimented Statistics Canada data collection on indicators of the socio-economic and land control variety will aid this research. We must also ask ourselves the question, raised by Chief Dean Sayers - if First Nations agree to this piece of legislation for its short-term socio-economic benefit of increased ownership and control, what will the long-term implications be?

For a full list of First Nations who have opted-in-to the First Nations Land Management Act, please see here.

If you are interested in learning more about practices of Anishinaabe research, consider attending the third bi-annual Anishinaabe Inendamowin Research Symposium, with the theme “Weaving Meaningful Anishinaabe Research Bundles”. It will take place on Friday, January 26, 2017 in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. For more information and registration, visit their website.

References

Canada Federal Government. (1999). First Nations Land Management Act. Retrieved from: http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/f-11.8/page-1.html.

Canada Federal Government. (1985). The Indian Act. Retrieved from: http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/PDF/I-5.pdf: Minister of Justice.

FAFNLM. (1996). Framework Agreement on First Nation Land Management. http://www.nalma.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Framework-Agreement-Amendment-5-edited.pdf.

Greg Richard, J. C. (2007). The High Costs of Doing Business on First Nations Lands in Canada. http://www.fiscalrealities.com/uploads/1/0/7/1/10716604/the_high_costs_of_doing_business_on_first_nation_lands_in_canada.pdf.

INAC . (2016, August). Land, Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. Retrieved from https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100022278/1100100022279

National Aboriginal Lands Managers Association. (2016). About Land Management. Retrieved from nalma.ca: http://www.nalma.ca/professional-development/about-land-management

S Cornell, J. K. (1992). Reloading the dice: Improving the chances of economic development on American Indian reservations. Los Angeles: University of California at Los Angeles.

[i] The First Nations Land Management Act was assented on June 17, 1999.

Jamie McIntyre’s given name is mashkiki kwe, and she belongs to makwa doodem (bear clan). She has a mixed background of settler Scottish and Anishinaabe from Batchewana First Nation. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in Community Economic and Social Development at Algoma University, and is currently a Resource and Partnership Developer at NORDIK Institute based in Sault Ste. Marie. Her interests include cross-cultural relationship building and knowledge sharing, as well as sustainable development practices.

The content of Northern Policy Institute’s blog is for general information and use. The views expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Northern Policy Institute, its Board of Directors or its supporters. The authors take full responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of their respective blog posts. Northern Policy Institute will not be liable for any errors or omissions in this information, nor will Northern Policy Institute be liable for any detriment caused from the display or use of this information. Any links to other websites do not imply endorsement, nor is Northern Policy Institute responsible for the content of the linked websites.

Northern Policy Institute welcomes your feedback and comments. Please keep comments to under 500 words. Any submission that uses profane, derogatory, hateful, or threatening language will not be posted. Please keep your comments on topic and relevant to the subject matter presented in the blog. If you are presenting a rebuttal or counter-argument, please provide your evidence and sources. Northern Policy Institute reserves the right to deny any comments or feedback submitted to www.northernpolicy.ca that do not adhere to these guidelines.