From Diversion to Reduction: Ontario's Vision for a Circular Economy

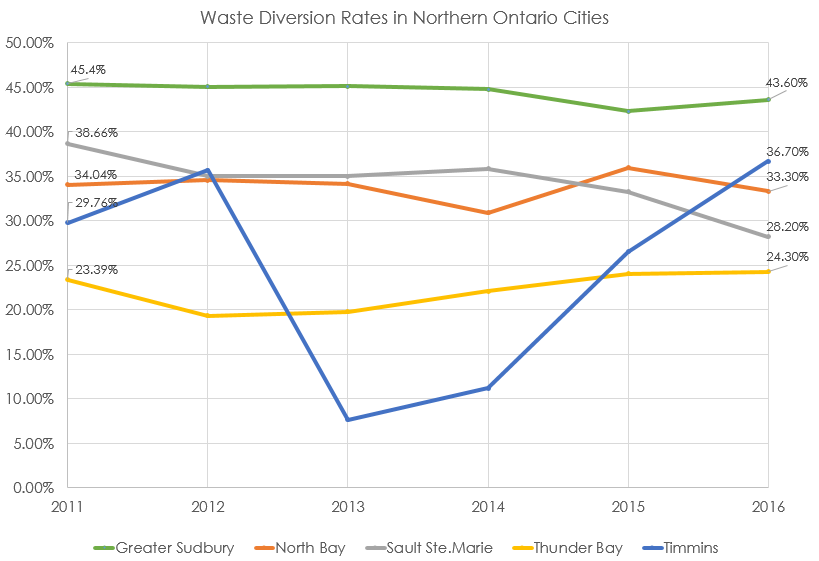

September 17, 2018 - In waste management, diversion refers to redirecting waste from the landfill to alternatives such as blue box and composting programs. Waste diversion is important because we have limited space for landfills and they contribute approximately 6 percent of the greenhouse gas emissions in Ontario. So how are we doing at diverting our waste in the North?

Figure 1 (Source: Resource Productivity & Recovery Authority Datacall)

As shown in Figure 1, diversion rates in several Northern cities are well below that of the 49.2 percent provincial average. Waste diversion programs can also be costly, (MacBride 2012) and common recyclables like plastic cannot be infinitely recycled. This is where waste reduction comes in. Reduction encompasses more than just curbside collection - it includes the quantity of goods, how they are made, packaged, and how they are returned to the economy after a first or second life. Achieving waste reduction can be much more difficult to achieve than diversion because it is not driven as much by policy and regulation as it is by market forces and consumer culture (Dewees and Hare 1999).

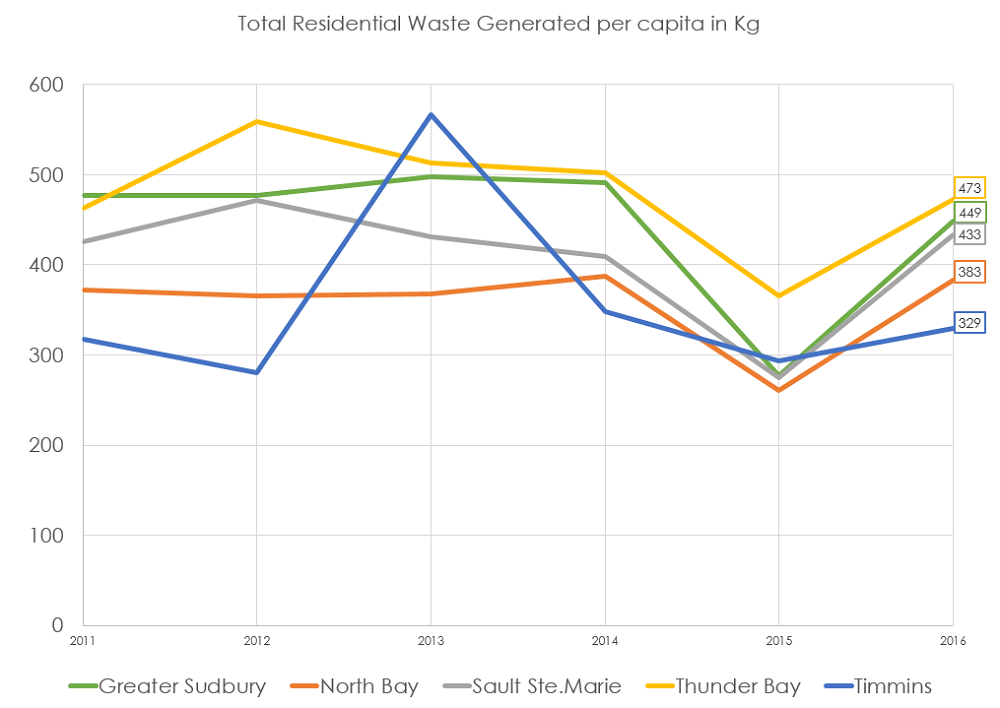

Figure 2 (Source: Resource Productivity & Recovery Authority Datacall)

Figure 2 (Source: Resource Productivity & Recovery Authority Datacall)

While waste generation amounts in the North vary from the provincial average of 354kg, as shown in Figure 2, they have all recently increased. In 2015, NPI published a blog criticizing the previous Waste Diversion Act (2002) for not prioritizing waste reduction and building on Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) policies. It would seem that the new Waste-Free Ontario Act (2016) now seeks to transition waste diversion programs toward a circular economy, through furtherance of EPR. A circular economy as defined by the Act consists of: “1. Minimiz[ing] the use of raw materials, 2. Maximiz[ing] the useful life of materials and other resources through resource recovery; and 3. Minimiz[ing] waste generated at the end-of-life of products and packaging.”

The accompanying Waste-Free Ontario Strategy states that we need to “fundamentally change the way we think about waste in Ontario.” Consider this: in nature there is no such thing as waste – life exists in cycles where all matter is transformed into other matter that is useful to the ecosystem (Hill 2017). Waste can be considered a process where humans transform goods into matter that holds a negative value and should arguably be considered in global economies as a form of market failure. The role of managing waste falls to local government, which in a way is a task that begins with absorbing debt. This is the rationale behind EPR, which shifts the cost of waste back upstream to the producers (MacBride 2012). In theory and as outlined by the strategy, EPR policies will eventually change the production quality of goods so that they need never become waste.

As they say, one man’s trash is another man’s treasure and it’s important to consider this in waste management policies seeking to support a circular economy. As cliché as that saying is, a comprehensive waste reduction system is one that recognizes that goods that may be worthless to one individual, may be worth something to another. Rather than wasting this matter, local governments can support systems that help to redistribute it to people who find value in it. For a circular economy to work, there must be avenues for the secondhand economy, in which 81 percent of Ontarians participated last year. Furthermore, according to Kijiji’s “Second-Hand Economy Index”, in 2017, 2.3 billion goods were granted a second, third, (or more) life through the secondhand economy in Canada.

While the new Ontario Waste-Free Strategy mentions community activities like yard sales and swap meets, it doesn’t offer realistic support for these types of activities that are part of the characteristics of a circular economy.

A potential program to accomplish this in Northern Ontario is a Local Exchange and Trade System (LETS), where alongside a local, community-created currency, goods and services are traded either directly for other goods and services or for the community currency. A community currency, is a type of complimentary currency created, distributed and usable only at a local level, say within a city or town. In Victoria BC, a case study on the VicLETS organization found that the system helped foster a culture of repurposing and recycling, preventing goods from going to landfill and instead recirculating them through the community while also cultivating community spirit and creating social bonds. While LETS have previously been paid more attention to by the field of economics, many people participate in LETS as an effort to be more environmental.

A possible model for a LETS in Northern Ontario is the Toronto-based barter and trade app, Bunz, which began as a Facebook group that allows its users to post items they no longer need or want, alongside a list of items they would accept in trade. As a popular free-to-use app, Bunz has introduced BTZ, a form of digital currency that can be used to trade with on the app, or to purchase things at several partner restaurants and stores in the Toronto area. The CEO of Bunz stated that the app is about decentralizing the economy, to “create a way that allows people to interact, while reducing the amount of value that’s extracted from them by large companies or entities.”

While the app is available globally, there is currently no ability to spend Bunz currency outside of Toronto. However, for local governments looking for systems that support the circular economy and reduce waste throughput, using Bunz as the blueprint for LETS, or even as the exact medium, could be an innovative option.

Sources

Dewees, Donald, and Michael Hare. 1999. Reducing, Reusing and Recycling: Packaging Waste Policy in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Centre for Public Management.

Hill, Pamela. 2017. Environmental Protection: What everyone needs to know. New York: Oxford University Press.

MacBride, Samantha. 2012. Recycling Reconsidered: The present failure and future promise of environmental action in the United States. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Ontario. 2018. Waste management What you need to know about how waste is managed in the province, including Ontario’s new waste-free Ontario framework. June 28. Accessed July 31, 2018. https://www.ontario.ca/page/waste-management.

Rachel Armstrong was a Policy Analyst Experience North Placement at Northern Policy Institute during the summer of 2018.

The content of Northern Policy Institute’s blog is for general information and use. The views expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Northern Policy Institute, its Board of Directors or its supporters. The authors take full responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of their respective blog posts. Northern Policy Institute will not be liable for any errors or omissions in this information, nor will Northern Policy Institute be liable for any detriment caused from the display or use of this information. Any links to other websites do not imply endorsement, nor is Northern Policy Institute responsible for the content of the linked websites.

Northern Policy Institute welcomes your feedback and comments. Please keep comments to under 500 words. Any submission that uses profane, derogatory, hateful, or threatening language will not be posted. Please keep your comments on topic and relevant to the subject matter presented in the blog. If you are presenting a rebuttal or counter-argument, please provide your evidence and sources. Northern Policy Institute reserves the right to deny any comments or feedback submitted to www.northernpolicy.ca that do not adhere to these guidelines.